In the course of some research I came across a working paper by A. Basso and S. Funari (dated September 2001) titled “A generalized performance attribution technique for mutual funds.”

Please don’t let the title fool you: this isn’t about performance attribution. Rather, it’s about risk-adjusted performance. But putting that aside …

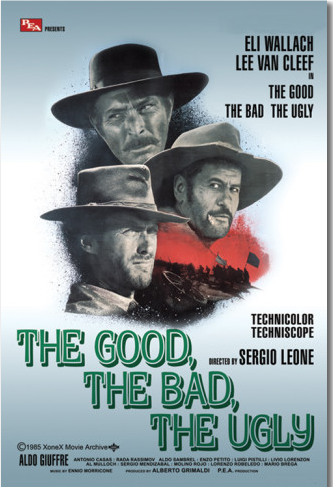

In the article they generally describe measures such as the Sharpe and Treynor ratios as “numerical indexes … that take into account an expected return indicator and a risk measure and synthesize them in a unique numerical value.” I happen to think that this description is excellent. The notion that the returns and risk measures are synthesized into a unique numerical value. Isn’t that an excellent description? Okay, so that’s the good.

The “bad,” in my view, is how the authors describe some of the results they obtained during their analysis. They used data from Italian mutual funds. During the period observed, “two bond funds … exhibit a negative mean excess return; this entails that the values of the Sharpe, reward to half-variance and Treynor indexes for these funds are negative and, above all, meaningless. In fact, when the excess return is negative these indexes can be misleading, since in this case the index with the higher value is sometimes related to the worse return-to-risk ratio.”

We’ve taken this matter up before; the realization that negative excess returns yield confusing Sharpe and Information ratios (as well as, apparently, other risk-adjusted measures). To refer to these results as “meaningless” and “misleading” is unfortunate, I believe. I’ll confess my own struggles with this, but believe that my earlier explanation (see for example the January 2012 edition of TSG’s monthly newsletter) provides some insights into the value and interpretation of the results.

When things don’t make sense, sometimes additional time is needed to reflect upon them. Again, I’ll confess my own typical impatience with such things. But time spent on these events can prove beneficial.

Performance Perspectives Blog

Learning to take the good with the bad