The headline in today’s Home News Tribune (a central New Jersey newspaper) is titled “Probe: Teachers enabled cheating.” It points out how last year Woodbridge administrators and teachers were celebrating because New Jersey state’s School Report Card reported impressive results for several township elementary schools in 2010. For example, Avenel Street Elementary, where 94 % of its third-graders scored “high marks.” This was quite a feat, since only 37 % of students statewide earned such scores. As it turned out, this was a case of teachers cheating.

Last week we learned that famed bicyclist Lance Armstrong was being stripped of his medals because of cheating.

I am often reminded of Charlie Sheen’s portrayal of a broker in the movie, Wall Street, who suddenly began racking up extraordinary impressive numbers. His success was largely attributed to insider trading.

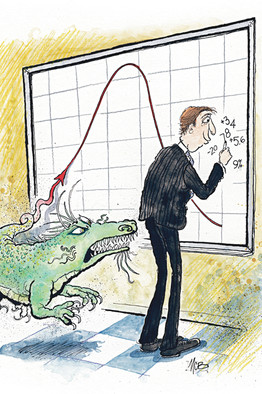

These are all examples of outliers. And while we can expect to see outliers, there are times when they are just a bit too exceptional. To have a school with 94% of its students achieve “high marks” when the norm is only 37% is just a bit too good; to win the Tour de France a string of seven times is just too good without the help of something illicit.

Americans will recall a few years back when in any given baseball season we’d find several batters hitting more than 50 or 60 home runs, something that used to be quite rare had become the norm. Some observers suggested that the balls were “juiced”; it turned out that the players were. Now that steroids are the exception in baseball, the numbers have dropped to the level they had historically been.

While not all distributions are normal, we still are sensitive (or should be) to events that are just too good. In one of his books (I can’t recall offhand which), Harvey Mackay speaks of things just being a bit too good; and when this happens, be careful.

Too often when exceptional events occur, we are slow to think that something improper has occurred; perhaps we are caught up in the moment, or really want to believe that someone can be that good. Who wants to be accused of being a “doubting Thomas” or a “party pooper,” raining on someone else’s parade?

A candidate for a “poster child” for exceptional behavior in investing would be Bernie Madoff: his string of above average returns should have caused concerns, from his clients and the regulators, but because everyone liked Bernie, hardly anyone questioned such performance.

In the late 1960s, my older brother, who died more than 20 years ago, came home from Army basic training, and showed me a photo of the woman he had just married (a complete surprise to all of us, since we didn’t even know he had a girlfriend). I knew there was a problem the moment I saw her picture: she was just too good looking for my brother. Sounds like a nasty remark for a brother to make, right? You have to understand that Bill was a bit awkard and clumsy, and wasn’t particuarly good looking himself. He had a difficult time attracting girls when we were growing up. And so, for him to find someone so attractive just didn’t seem right. As it turned out, this was an older woman who had been married before, to soldiers who had gone off to Vietnam (where my brother was expected to go, but didn’t), never to return, and so she’d collect the life insurance money. A sad story, yes? I won’t bother to share any further details about what transpired, but only to say that this was an outlier and one that I, at a fairly early age, was able to detect.

In our GIPS(R) (Global Investment Performance Standards) verifications, we look for outliers, as these are often cases of errors that crept in. And while outliers are often and perhaps usually fine, there are times when they aren’t. Consequently, we should be sensitive when they occur, just in case …

Performance Perspectives Blog

Beware of outliers: lessons from education, sports, and movies