Despite the criticisms that have been offered to anyone who wishes to make predictions, there is no limit to their presence. Who would want to see the end of weathermen (weather people?) telling us what tomorrow will look like, despite everyone knowing “no one can [accurately] predict the weather.”

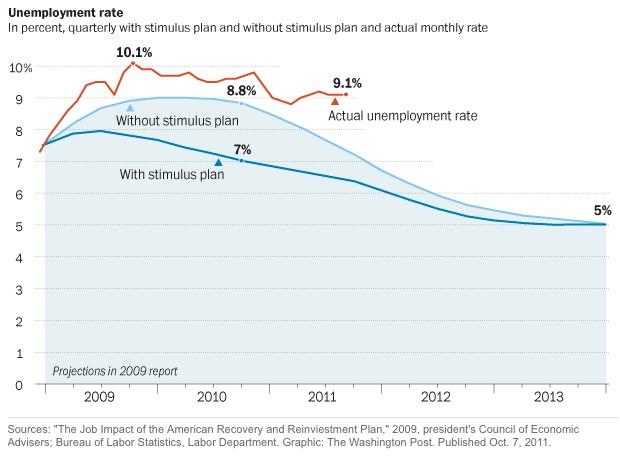

The accompanying chart shows the Obama administration’s predictions for what the unemployment rate would be if (a) the stimulus package was implemented, (b) what it would be if it wasn’t implemented, and (c) what it actually has been. The abject failure to be accurate in these predictions has resulted in strong criticism from the president’s foes (and even some friends). But Obama isn’t the first president to make predictions (or for that matter, promises) that didn’t hold (recall, for example, “read my lips: no new taxes!”).

Qualifying predictions is important. I recall a few years ago when a couple sports pundits didn’t bother to offer their predictions for the first round of the baseball league playoffs, as it was “a given” as to what teams would prevail in the first round. Well, they were wrong. And yet, their pomposity and arrogance seemed to give their predictions undeserved credibility.

I have voiced my concerns with ex ante risk measures, but recognize that clients and managers still want to see them, which is fine, as long as they recognize the underlying assumptions and the qualifications of these predictions. To make bold statements about what will happen will usually lead to errors of one sort or another.