I recently conducted a software certification for a software vendor. I found some issues with their application of rates of return, and we’ve been going back-and-forth on it. One issue that arose was my belief that money-weighting is the appropriate approach for subportfolio rates of return [I should point out that this isn’t a requirement for a vendor to pass, only our belief; we recognize that TWRR sadly “rules” at all levels today; we simply try to enlighten our clients into the appropriateness of alternative approaches]. As a way to demonstrate this, I offered the following scenario:

- Day 1: a portfolio holds 100 shares security X, valued at $10 per share (value = $1,000)

- Day 2: the stock price drops to $5 per share, and the manager buys 1,000 additional shares (contribution = $5,000)

- Day 3: the stock price has risen to $11 per share; the manager now owns 1,100 shares (value = $12,100).

What’s the rate of return? Well, if we use time-weighting, revaluing for the large flow on Day 2, we’ll get a return of 10%, even though it’s evident that there was a much larger gain. If we use Modified Dietz (without revaluing) we get 174.29%, and the IRR gives us 218.16 percent.

Inconsistent Rates of Return

My client responded by suggesting that if the portfolio only held this stock, and that on Day 2 there was an external cash flow that caused the purchase, by using MWRR at the subportfolio and TWRR at the portfolio we’d get “inconsistent” rates of return:

- Portfolio ROR = 10%

- Subportfolio ROR = 218.16%

How could we possibly explain this to a client?

Great question!

At the portfolio level, we are reporting on the portfolio manager’s return. Since she does not control client-directed, external cash flows (contributions and withdrawals), she cannot be given any credit for the timing or size of these flows; therefore, we eliminate their impact, and the manager gets a 10% return.

At the subportfolio level, however, we do take the (internal) cash flows into consideration, because the manager does control them. When the additional $5,000 came in, she saw that the stock price had dropped, and thinking that this was a temporary shift, decided to invest it all into the same security; as it turns out, this was a wise move, and so she benefited from the price increase that occurred the following day. She should be rewarded for this decision.

We are measuring two different things. Beginning in 1966 (with the publication of Peter Dietz’s doctoral dissertation), the industry has recognized that time-weighted rates of return are appropriate to judge the manager at the portfolio level.

Sadly, despite Dietz’s and others’ recognition that money-weighted rates of return had a place, too, the IRR was almost completely abandoned until fairly recently (which my colleagues Steve Campisi, CFA; Stefan Illmer, PhD and I take some credit for). We are now seeing a resurgence in the use of the IRR.

Why inconsistency works

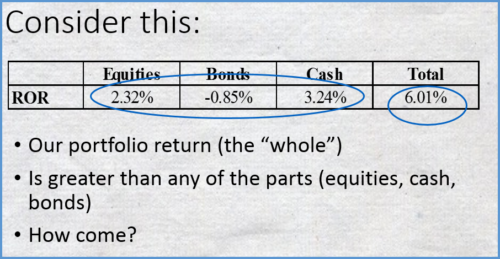

I thanked our client for raising this point, although I had raised it before myself. Consider this scenario, which comes from our Fundamentals of Investment Performance class:

What do we see? Well, what I think are numbers that simply do not make sense: our portfolio has a return of 6.01%, but the underlying asset classes have returns that fall far below this level, with none even above 3.25 percent. What is going on?

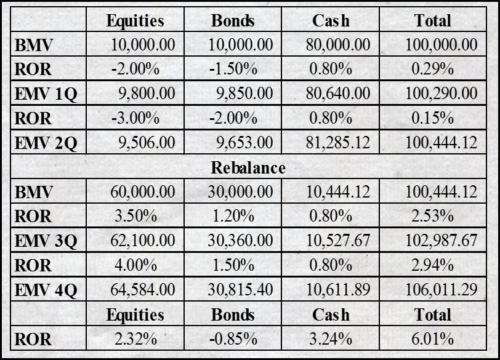

Well, let’s look at the portfolio details:

As you can see, the manager decided to keep most of the portfolio in cash at the start of the year, which turned out to be a wise move, as both stocks and bonds didn’t do well. However, at mid-year he decided to shift money into both of these sectors, just at the right time, as it turns out. As a result, there was a significant gain overall. However, because time-weighting eliminates the effect of cash flows, the underlying sectors produce results that belie the effects of the internal cash flow decisions.

But, as our client would suggest, at least we’re being consistent! We’re consistently showing time-weighted rates of return, which apparently is something to find worthy, despite the failure of the method to capture the results of the manager’s decision, and fail to produce meaningful results. But, we’re consistent.

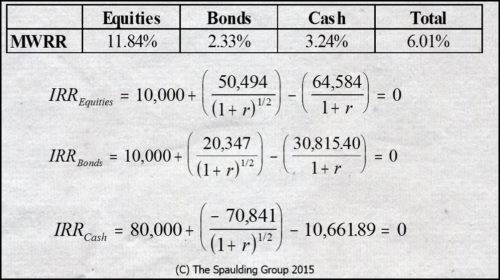

I’m all for consistency, but only when it truly makes sense; at times we need inconsistency, and here’s one. Let’s recalculate our subportfolio rates of return using the IRR:

Aren’t these results more meaningful? Don’t they capture what went on at the subportfolio level?

The truth is that I’ve been showing this example for more than a decade, and usually it’s met with understanding and appreciation. However, like our client, on occasion someone criticizes the “inconsistency,” and states that by doing this we are not able to tie the numbers back to the portfolio, or “reconcile” to its return.

“Really?” is my typical response. “Please then explain how you’d ‘reconcile’ the ‘consistent” TWRR results?”

You can’t.

- They’re nonsensical.

- They’re inappropriate.

- They’re simply wrong!!!

Time-weighting belongs in one place and one place only: at the portfolio level, when reporting on how the manager did. That’s it. Simple.

Money-weighting belongs at the portfolio level, to show (a) how the manager did in those cases where the manager controls the flows (e.g, private equity) and (b) to explain to the client how they did, as a result of their cash flow decisions, coupled with the manager’s investment decisions. It also belongs at the subportfolio level, because the manager controls these flows.

Inconsistency isn’t always a bad thing … well, perhaps at times:

As always, your thoughts are welcome.

Oh, and I should point out that time-weighting also applies at the composite level, when producing returns for GIPS(R) (Global Investment Performance Standards), but this is arguably only an extension of the portfolio rates of return; hope you agree!