Issue Contents:

The GIPS® Standards and

the Smith Machine

by David Spaulding, DPS, CIPM

Chances are, if you’ve been to gyms such as Planet Fitness® you’ve encountered a Smith Machine. It provides a way to lift free weights in a more controlled and safer fashion.

Chances are, if you’ve been to gyms such as Planet Fitness® you’ve encountered a Smith Machine. It provides a way to lift free weights in a more controlled and safer fashion.

I joined the Planet Fitness in Burlington, Canada, where I reside for about half the year. I hesitated for a long time to try it out, because it looked just a bit too complicated. One day I committed to doing this, but first went to, as my soon-to-be-wife likes to call it, the University of YouTube. There, I found many videos that explained how the machine works and how to engage with it. I’m now a fan.

At the gym in our community center in Naples, FL (where we live the rest of the year) there’s a Smith Machine, as well. The problem was it was pushed too far against one of the walls, making it challenging to use properly. But that didn’t seem to phase anyone as they simply used it backwards (that is, instead of putting the weights back onto the rack by rolling their hands forward, they faced the other way and rolled their hands backwards. I think this isn’t as natural and, perhaps, even unsafe.

And so, I contacted the community center’s office and asked if it was possible to pull the machine a few inches away from the wall. I explained how I felt it was not being used properly because there wasn’t enough room; but, by pulling it back, it could be. They did, which I was very pleased with. Whenever I use it, the first thing I discover is that the bench is facing the wrong way (i.e., whoever was there before me used it backwards). I turn the bench around, use it the right way, and leave the bench in the right direction. Only to find, the next time I arrive, that the bench is, once again, facing the wrong way.

Why is this?

Well, because those who use it have been using it backwards for years (without knowing it); this is what they do; they may even be surprised or upset that they must rotate it back to the other direction. When you get used to doing something, year after year, it creates a groove, so to speak, and it’s difficult to change.

Well, the same thing has occurred with rates of return, as I’ll explain.

Let’s begin with the basics.

While what appears here is probably well known, it’s helpful to place here, as it is the basis for what follows.

Time-weighting

Peter Dietz introduced the concept of time-weighting1 in 1966. Prior to that, he found that most pension funds used the IRR to evaluate the performance of their managers. But since they, the pension funds, controlled the cash flows, he argued that using a metric that might benefit or penalize the manager because of the pension fund’s good or bad cash flow decisions was unfair and inappropriate.

With the BAI championing this idea, it became pretty standard for firms. Perhaps too standard, as many had forgotten the value of the internal rate of return.

Money-weighting

The IRR is a form of money-weighting; unlike time-weighting, it takes the flows into consideration, and is therefore quite appropriate in two cases.

First, to evaluate the performance of managers who control the flows. Private equity is a perfect example, as their clients commit capital to be managed; but, until the manager (the general partners) needs the funds (for investments or expenses), the cash stays with the client (the limited partner). The manager will do drawdowns or capital calls when necessary; and, will return funds to the clients at various stages of the partnership.

Since the manager controls the flows, it is standard practice to use money-weighting. Prior to the 2020 version of the GIPS standards, the IRR was the only formula supported; with the new version, the broader term “money-weighted” is used, which I think is unfortunate, but that’s for another time.

The second case for using money-weighting is for the owner of the asset. This owner can be a pension fund, endowment, high net worth individual, or even a mutual fund shareholder. It’s the party that gave their money to the manager to invest for them. Since these owners typically control the flows, a money-weighted return would help them learn how they did.

In North America, many retail clients are given “personal rates of return” by their mutual fund companies, so the investors can understand how the timing of their cash flows impacted their investments.

But don’t most pension funds and other asset owners calculate time-weighted returns as standard practice?

Yes! They do. And why is this?

I believe they started doing this years ago, perhaps when Peter Dietz and the BAI championed Time-weighting. What these organizations failed to realize was that both Dietz and the BAI were speaking of a return method for their managers; not for them.

There are many articles in my library from the 1960s and 1970s that speak to this phenomenon.

Many tried to educate pension funds and others that they needed two metrics: time-weighting for their managers,2 money-weighting for themselves.

Now, decades later, many of these plans are still using the time-weighted method to evaluate their overall plan. Just like the users of the Smith Machine at my local facility in Naples, they’ve been doing it the wrong way for so long they don’t even realize it. And since this is common with their peers, it only makes sense to do the same.

The Room Where It Happened

To paraphrase Leslie Odom, Jr. and Lin-Manual Miranda (as in Hamilton), I wasn’t in the room where it happened, so I do not have first [or even second] account knowledge; I can only imagine.

And what do I imagine happened? The decision to require asset owners who wish to comply with the GIPS standards to report time-weighted returns. Given that many of the representatives from asset owner organizations were probably using time-weighting, it would seem quite logical that the Standards require it. It made abundant sense.

What prompted this piece in the first place?

In the past two weeks, I’ve worked with two new clients in the Middle East. For one, I conducted our firm’s GIPS Planning Session™.3 For the second, it’s been a broader assignment, where they intend to comply with the Standards at some point in the future.

I was impressed with the first client, who fully got the value of the internal rate of return (IRR). They calculate no time-weighted returns, as they want to know how they performed. Since they control the cash flows, they want a metric that captures them. Exactly!

The second client calculates time-weighted returns at the total fund level, but in order to achieve GIPS compliance, must make a number of changes; the details are unimportant. Today, they only calculate the IRR for private equities.

To comply with the GIPS standards, the first client must introduce time-weighting, to calculate the total fund’s time-weighted return. This composite is made up mainly of illiquid assets, many of which are private equities. Yes, there are some public assets, as well.

For the second, they must also calculate the time-weighted return for their total fund. And so, when they get the result, what will it represent? What’s its meaning? How do we interpret it?

What’s the problem?

Money-weighting takes flows into consideration; time-weighting eliminates or reduces their impact.

And so, when we calculate the return for a total fund, again what does it represent? What question does it provide the answer to?

For example, let’s say we get a return for 2023 of 15.45 percent. How do you interpret this number? How do you explain it? What question is it answering?

It seems to me there are only two possible questions: first, “how did the manager(s) do?” But this plan is comprised of both public and private assets; to judge the private equity managers, standard practice is to use money-weighting; but here, we’re lumping these assets together with the publics. Why would we use time-weighting? Would we use time-weighting at any time for a private equity fund by itself? If yes, why? What would the result mean?

The second question, “how did we, the plan, do?” Well, as noted earlier, to do this we would use the IRR, since we want to capture the cash flows. But we’re totally eliminating the flows’ impact on performance.

And so, what does the result mean or represent? What question are we answering?

Does anyone get this?

Yes, fortunately. My first client noted above clearly does. And, in the United States, the Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB) mandates that public pension funds report the IRR on an annual basis. Unfortunately, because so many performance measurement professionals and their managers are used to time-weighting, the IRR seems like a foreign concept, which is unfortunate.

So, what can we do?

If you are at all persuaded by this argument, you, like me, may be frustrated by the reality that asset owners are forced to report what I think are nonsensical figures. At present, I don’t think there’s anything to do. Perhaps when the Standards undergo yet another revision (2030?), those who oversee them might be open to doing a “180,” and moving away from time-weighting and to money-weighting. Or, perhaps, at least give asset owners a choice which to use.

The Standards do recommend that asset owners also calculate a money-weighted return, but this is optional, as time-weighting is still mandated.

As with many things, we need to educate.

Our firm was successful in educating performance measurement professionals about the Brinson-Fachler attribution method, versus the Brinson, Hood, Beebower. Prior to the introduction of our training classes, 25 years ago, the BHB ruled; today, it’s BF. It wasn’t just our classes, we and others have penned many articles on this in The Journal of Performance Measurement.® Once more and more “got it,” the BHB was pushed aside and is now used by less and less firms. Please feel free to comment. And if, perchance, you can offer a meaningful question to align with the total plan’s time-weighted return, or explain what it actually represents, “I’m all ears!”

Note that this isn’t the only GIPS standard metric I’ve criticized. I’ve argued that the aggregate method for composite construction not only violates the definition of a composite return, but has the potential to result in nonsensical results. The asset-weighted standard deviation, which the AIMR-PPS® (AIMR Performance Presentation Standards) encouraged yields a result that no one can explain. Fortunately the GIPS standards do not recommend it, but they also don’t discourage its use: they should.

The Standards are very important. Not only have they been adopted by most investment managers, but they are also becoming more widely adopted by asset owners around the globe. We support this. We only wish they could do a few things a bit better.

- In his dissertation, Pension Funds: Measuring Investment Performance. He did not coin the term time-weighting, however; that was done by the Bank Administration Institute two years later, when they published their Measuring the Investment Performance of Pension Funds.

- Back then, private equity investing was not common, so the notion of using the IRR for the manager would have not applied in most cases.

- This is an optional day where the our verifier conducts training, a gap analysis, and other activities to help a new client proceed towards compliance with the GIPS standards. To learn more about this, please contact Chris Spaulding (CSpaulding@TSGperformance.com).

Have an opinion? Please share it with Patrick Fowler.

Quote of the Month

“Confidence is the sweet spot between arrogance and despair.”

— Rosabeth Moss Kanter

GIPS® Tips

Experience White Glove GIPS® Standards Verification with TSG

Are you tired of being treated like just another number by your GIPS verifier? At TSG, we prioritize your satisfaction and success above all else.

Partnering with us means gaining access to a team of seasoned GIPS specialists dedicated to delivering unparalleled service and exceptional value. Whether you’re seeking a new verifier, preparing for your initial verification, or just starting to explore GIPS compliance, TSG is the best choice.

Why Choose TSG?

Unmatched Expertise: Our experienced team brings unmatched proficiency in GIPS standards, ensuring thorough and efficient (not “never-ending”) verifications.

Personalized Support: We understand that the journey toward GIPS compliance is complex. That’s why we offer ongoing support and guidance as needed, as well as access to a suite of exclusive proprietary tools, designed to make compliance and verification as easy as possible for you and your firm.

Actionable Insights: When you choose TSG, you will work with ONLY highly experienced senior-level GIPS and performance specialists. Their expertise translates into actionable advice, helping you navigate the complexities of the Standards in the most ideal way for your firm.

Hassle-Free Experience: At TSG, we guarantee your satisfaction and we do not lock our clients into long-term contracts.

Ready to Experience the TSG Difference?

Take the first step towards a better GIPS standards verification. Schedule a call or request a no-obligation proposal today at GIPSStandardsVerifications.com.

The Journal of Performance Measurement®

This month’s article brief spotlights “Monetizing Excess Returns” by David D. Spaulding, CIPM of TSG and Terry Honner, CIPM of Investment Management Corporation of Ontario, which was published in volume 28, issue #2 of The Journal of Performance Measurement. You can access this article by subscribing (for free) to The Journal (link below). To confirm your email address, click the graphic below. If you’re a subscriber but haven’t received a link the the current issue, please reach out to Doug Spaulding at DougSpaulding@TSGperformance.com.

At various venues over the years, we have observed increased interest in seeing excess returns expressed in monetary terms (e.g., dollars). The idea for this is pretty straightforward: knowing that we outperformed the benchmark by X%, what is the equivalent gain in dollar terms? The challenge comes into play when we deal with time-weighting, since time-weighted returns don’t necessarily align with the actual amounts earned or lost during a period (e.g., we might lose money but have a positive return). This is because time-weighted returns seek to eliminate or reduce the impact of cash flows. In this article we will review a rather simple method to monetize returns, review cases where the results may not appear intuitive, address the timing of “resetting” values, and offer an alternative to time-weighting that should be considered.

ATTN: TSG Verification Clients

As a reminder, all TSG verification clients receive full unlimited access to our Insiders.SpauldingGrp.com site filled with tools, templates, checklists, and educational materials designed to make compliance and verification as easy as possible for you and your firm.

Contact CSpaulding@TSGperformance.com if you have any questions or are having trouble accessing the site.

Also, as a client, you are entitled to one complimentary pass to PMAR 2024. Contact Andrew Tona to reserve your space.

TSG Milestones

Join us for a 5K on Day 2 of the PMAR Conference!

The Sandra Hahn-Colbert 5K Run/Walk will take place on May 23rd at 7:15 AM. The route will take us through downtown New Brunswick and into Johnson Park along the northern banks of the Raritan River. In addition to the 5K, we’ll be offering a 1-1.5 mile walk. All participants will receive a finisher coin. If you have any questions, or you’d like to register early, please contact Doug Spaulding at DougSpaulding@TSGperformance.com.

For more information on the PMAR Conference, click here, https://tsgperformance.com/events/pmar/.

PUZZLE TIME

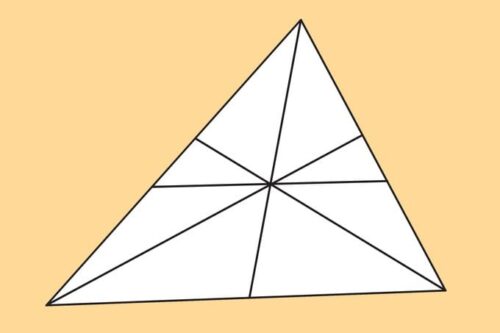

Here’s this month’s puzzle; Solution in the next issue!

How many triangles can you see?

Last month’s puzzle and solution.

Find the next two numbers in the series …

19 16 1 21 12 4 9

Answer:

19 16 1 21 12 4 9 14 7

The numbers correspond to letters, 1=a; 2=b; 3=c; etc.

It spells out SPAULDING

So, the next two in the series would be N and G, thus 14 and 7.

Thank you Anthony Howland for the puzzle.

Please submit your puzzle solution or puzzle ideas to Patrick Fowler.

Compliance Corner

SEC Marketing Rule FAQ: Use of Subscription Facilities Creates Complexity for Advisers Presenting Gross and Net Fund Performance

Authors: Christine Ayako Schleppegrell, Steve Stone, Christine Lombardo, Robert Raghunath of Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP

The SEC Division of Investment Management (the “Staff”) published an FAQ on February 6, 2024 (the “FAQ”) that will impact, and could create challenges for, the way an SEC-registered investment adviser calculates and presents in an advertisement the performance of a private fund that uses a subscription facility or other indebtedness secured by unfunded capital commitments of private fund investors (a “Subscription Facility”). The FAQ provides guidance about a provision under the SEC’s rule governing investment adviser advertising, Rule 206(4)-1 under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (the “Marketing Rule”) which generally prohibits an adviser from presenting in an advertisement a client portfolio’s performance gross of fees and expenses without also presenting the performance net of such fees and expenses: 1) presented at least as prominently as the gross performance; and 2) calculated over the same time period and using the same type of return and methodology as the gross performance (the “Time and Methodology Requirement”).

In the FAQ, the Staff indicates that the Time and Methodology Requirement applies to performance of private funds that use a Subscription Facility in the same way it applies to private funds without one. Although the application of the Time and Methodology Requirement to a private fund with a Subscription Facility may appear straightforward, financing a fund’s investments using capital borrowed from a Subscription Facility instead of limited partner capital could cause the fund’s gross performance to be calculated over a different time period and using a different methodology than the fund’s net performance. For example, an adviser may calculate a fund’s gross performance in a way that purely shows the performance of the fund’s investments An adviser might do this by using portfolio investments’ cashflows and distributions that do not reflect the source of the capital used to fund the investment (i.e., capital from an investor versus from a Subscription Facility). The adviser might then calculate net performance in a manner that illustrates how an investor’s dollars performed by using cashflows that distinguish whether capital is drawn from a Subscription Facility or an investor. This approach could result in the net performance reflecting the impact of the Subscription Facility, while the gross performance would not. Timing calculation issues could also arise if a private fund draws down capital from the Subscription Facility to make the fund’s initial portfolio investment, but at a later date issues its first capital call to fund investors to make subsequent investments or pay down borrowings from the Subscription Facility. This timing mismatch could cause gross and net performance to be calculated over different time periods because, in such example, the adviser calculates gross performance of the fund starting at the time of the fund’s initial contribution to a portfolio investment (which would likely be shortly following the fund’s initial drawdown from the Subscription Facility), in contrast with net performance which advisers typically begin calculating at the point investor capital is first called by the fund.

To attempt to resolve these conflicts, an adviser could consider presenting both gross and net fund performance without the impact of borrowing from the Subscription Facility (i.e., on an unlevered basis). Alternatively, an adviser could consider presenting both gross and net fund performance by reflecting the effects of the borrowing (i.e., on a levered basis), as long as the performance is accompanied by appropriate disclosures describing the impact of any Subscription Facility used. Advisers should ensure they are calculating both gross and net performance over the same time period. This starting point could be on or around the date of the fund’s first drawdown from a Subscription Facility assuming the Subscription Facility (and not investors) provided the capital for the fund’s initial investment. These calculation nuances and the required assumptions could also be exaggerated when presenting returns of individual portfolio investments, or other types of extracted performance, as opposed to the returns of an entire fund’s portfolio.

Aligning the calculation time periods and methodologies of a fund’s gross and net performance could force advisers to make assumptions that deviate from a fund’s actual experience, which could trigger the need to make more extensive and complex disclosures about the calculation of levered or unlevered gross and net returns. For example, an adviser should disclose if it calculates gross and net performance by artificially matching the timing of investor cashflows with Subscription Facility cashflows.

While determining how to comply with the FAQ, advisers may consider the requirements for calculating levered and unlevered fund performance under the SEC’s Private Fund Quarterly Statements Rule (Rule 211(h)(1)-2 under the Advisers Act, “Quarterly Statements Rule”), which is part of the SEC’s recently adopted Private Fund Advisers rulemaking. In particular, the Quarterly Statements Rule requires illiquid private fund performance in quarterly investor statements to be presented with and without the impact of any Subscription Facility. Advisers should bear in mind that, although the Quarterly Statements Rule requires advisers to compute illiquid private fund performance on both a levered and unlevered basis, for purposes of their marketing materials, advisers should be able to follow the FAQ’s guidance by presenting fund net performance only on an unlevered basis, or only on a levered basis (with appropriate disclosures).

Thank you to our friends at Morgan Lewis for contributing this article.

Book Review

Edison, by Edmund Morris

Review by David D. Spaulding, DPS, CIPM

One of my favorite genres is biographies, many of historical figures. I had read two of Edmund Morris’ three biographies of Theodore Roosevelt, and so when I discovered he’d written one on Thomas A. Edison, someone I wanted to learn more about, I thought it would be enjoyable. To some extent, it was; but to another, painful.

Painful in the degree of detail in which the author goes to discuss some of his inventions: much more detail than, I suspect, most people care for. “Just give me the basics” is often my mantra.

The book is oddly constructed, in that it goes backwards. It begins with the period 1920-1929, then 1910-1919, followed by 1900-1909, and so on, each taking up approximately 10 years. Why? I don’t know the answer, and the author has passed, so I can’t ask (someone probably did).

I learned how extensive Edison’s interests ranged; when he struck upon a subject, he focused and dedicated the time to master it. He was creative beyond imagination. He thought nothing of working 18- or more hour days, somewhat to the chagrin of his family who missed his presence.

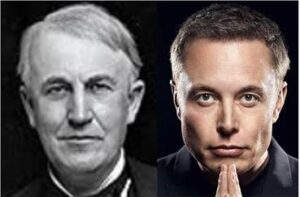

I happen to be listening to Walter Isaacson’s Elon Musk, and the comparison is amazing, in so many ways. Musk shares so many traits with the great inventor, including simultaneously focusing on two or more very different areas. Musk, too, is legendary for the many hours he dedicates.

I am struck by the similarities in the photographs the authors used for the covers of their books:

Can you not see the focus, seriousness concentration they both display?

Unlike Musk, Edison was not wealthy. Granted, there were times when he was, to use the author’s term, “flush,” but since he often used his money to fund his projects, he was often in or near debt (even bankruptcy). He didn’t appear to be as skilled a businessman as Musk, especially when it came to managing and controlling his many patents.

I’m sure someone will eventually pen something that goes into a detailed comparison of these two very gifted men.

As for the Edison book, would I recommend it? Sorry, but no. Unless you love getting into the weeds or, perhaps, skilled at skimming. The Musk book? I’ll have more to say at another time.

The GIPS® Standards and

the Smith Machine

by David Spaulding, DPS, CIPM

Chances are, if you’ve been to gyms such as Planet Fitness® you’ve encountered a Smith Machine. It provides a way to lift free weights in a more controlled and safer fashion.

Chances are, if you’ve been to gyms such as Planet Fitness® you’ve encountered a Smith Machine. It provides a way to lift free weights in a more controlled and safer fashion.

I joined the Planet Fitness in Burlington, Canada, where I reside for about half the year. I hesitated for a long time to try it out, because it looked just a bit too complicated. One day I committed to doing this, but first went to, as my soon-to-be-wife likes to call it, the University of YouTube. There, I found many videos that explained how the machine works and how to engage with it. I’m now a fan.

At the gym in our community center in Naples, FL (where we live the rest of the year) there’s a Smith Machine, as well. The problem was it was pushed too far against one of the walls, making it challenging to use properly. But that didn’t seem to phase anyone as they simply used it backwards (that is, instead of putting the weights back onto the rack by rolling their hands forward, they faced the other way and rolled their hands backwards. I think this isn’t as natural and, perhaps, even unsafe.

And so, I contacted the community center’s office and asked if it was possible to pull the machine a few inches away from the wall. I explained how I felt it was not being used properly because there wasn’t enough room; but, by pulling it back, it could be. They did, which I was very pleased with. Whenever I use it, the first thing I discover is that the bench is facing the wrong way (i.e., whoever was there before me used it backwards). I turn the bench around, use it the right way, and leave the bench in the right direction. Only to find, the next time I arrive, that the bench is, once again, facing the wrong way.

Why is this?

Well, because those who use it have been using it backwards for years (without knowing it); this is what they do; they may even be surprised or upset that they must rotate it back to the other direction. When you get used to doing something, year after year, it creates a groove, so to speak, and it’s difficult to change.

Well, the same thing has occurred with rates of return, as I’ll explain.

Let’s begin with the basics.

While what appears here is probably well known, it’s helpful to place here, as it is the basis for what follows.

Time-weighting

Peter Dietz introduced the concept of time-weighting1 in 1966. Prior to that, he found that most pension funds used the IRR to evaluate the performance of their managers. But since they, the pension funds, controlled the cash flows, he argued that using a metric that might benefit or penalize the manager because of the pension fund’s good or bad cash flow decisions was unfair and inappropriate.

With the BAI championing this idea, it became pretty standard for firms. Perhaps too standard, as many had forgotten the value of the internal rate of return.

Money-weighting

The IRR is a form of money-weighting; unlike time-weighting, it takes the flows into consideration, and is therefore quite appropriate in two cases.

First, to evaluate the performance of managers who control the flows. Private equity is a perfect example, as their clients commit capital to be managed; but, until the manager (the general partners) needs the funds (for investments or expenses), the cash stays with the client (the limited partner). The manager will do drawdowns or capital calls when necessary; and, will return funds to the clients at various stages of the partnership.

Since the manager controls the flows, it is standard practice to use money-weighting. Prior to the 2020 version of the GIPS standards, the IRR was the only formula supported; with the new version, the broader term “money-weighted” is used, which I think is unfortunate, but that’s for another time.

The second case for using money-weighting is for the owner of the asset. This owner can be a pension fund, endowment, high net worth individual, or even a mutual fund shareholder. It’s the party that gave their money to the manager to invest for them. Since these owners typically control the flows, a money-weighted return would help them learn how they did.

In North America, many retail clients are given “personal rates of return” by their mutual fund companies, so the investors can understand how the timing of their cash flows impacted their investments.

But don’t most pension funds and other asset owners calculate time-weighted returns as standard practice?

Yes! They do. And why is this?

I believe they started doing this years ago, perhaps when Peter Dietz and the BAI championed Time-weighting. What these organizations failed to realize was that both Dietz and the BAI were speaking of a return method for their managers; not for them.

There are many articles in my library from the 1960s and 1970s that speak to this phenomenon.

Many tried to educate pension funds and others that they needed two metrics: time-weighting for their managers,2 money-weighting for themselves.

Now, decades later, many of these plans are still using the time-weighted method to evaluate their overall plan. Just like the users of the Smith Machine at my local facility in Naples, they’ve been doing it the wrong way for so long they don’t even realize it. And since this is common with their peers, it only makes sense to do the same.

The Room Where It Happened

To paraphrase Leslie Odom, Jr. and Lin-Manual Miranda (as in Hamilton), I wasn’t in the room where it happened, so I do not have first [or even second] account knowledge; I can only imagine.

And what do I imagine happened? The decision to require asset owners who wish to comply with the GIPS standards to report time-weighted returns. Given that many of the representatives from asset owner organizations were probably using time-weighting, it would seem quite logical that the Standards require it. It made abundant sense.

What prompted this piece in the first place?

In the past two weeks, I’ve worked with two new clients in the Middle East. For one, I conducted our firm’s GIPS Planning Session™.3 For the second, it’s been a broader assignment, where they intend to comply with the Standards at some point in the future.

I was impressed with the first client, who fully got the value of the internal rate of return (IRR). They calculate no time-weighted returns, as they want to know how they performed. Since they control the cash flows, they want a metric that captures them. Exactly!

The second client calculates time-weighted returns at the total fund level, but in order to achieve GIPS compliance, must make a number of changes; the details are unimportant. Today, they only calculate the IRR for private equities.

To comply with the GIPS standards, the first client must introduce time-weighting, to calculate the total fund’s time-weighted return. This composite is made up mainly of illiquid assets, many of which are private equities. Yes, there are some public assets, as well.

For the second, they must also calculate the time-weighted return for their total fund. And so, when they get the result, what will it represent? What’s its meaning? How do we interpret it?

What’s the problem?

Money-weighting takes flows into consideration; time-weighting eliminates or reduces their impact.

And so, when we calculate the return for a total fund, again what does it represent? What question does it provide the answer to?

For example, let’s say we get a return for 2023 of 15.45 percent. How do you interpret this number? How do you explain it? What question is it answering?

It seems to me there are only two possible questions: first, “how did the manager(s) do?” But this plan is comprised of both public and private assets; to judge the private equity managers, standard practice is to use money-weighting; but here, we’re lumping these assets together with the publics. Why would we use time-weighting? Would we use time-weighting at any time for a private equity fund by itself? If yes, why? What would the result mean?

The second question, “how did we, the plan, do?” Well, as noted earlier, to do this we would use the IRR, since we want to capture the cash flows. But we’re totally eliminating the flows’ impact on performance.

And so, what does the result mean or represent? What question are we answering?

Does anyone get this?

Yes, fortunately. My first client noted above clearly does. And, in the United States, the Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB) mandates that public pension funds report the IRR on an annual basis. Unfortunately, because so many performance measurement professionals and their managers are used to time-weighting, the IRR seems like a foreign concept, which is unfortunate.

So, what can we do?

If you are at all persuaded by this argument, you, like me, may be frustrated by the reality that asset owners are forced to report what I think are nonsensical figures. At present, I don’t think there’s anything to do. Perhaps when the Standards undergo yet another revision (2030?), those who oversee them might be open to doing a “180,” and moving away from time-weighting and to money-weighting. Or, perhaps, at least give asset owners a choice which to use.

The Standards do recommend that asset owners also calculate a money-weighted return, but this is optional, as time-weighting is still mandated.

As with many things, we need to educate.

Our firm was successful in educating performance measurement professionals about the Brinson-Fachler attribution method, versus the Brinson, Hood, Beebower. Prior to the introduction of our training classes, 25 years ago, the BHB ruled; today, it’s BF. It wasn’t just our classes, we and others have penned many articles on this in The Journal of Performance Measurement.® Once more and more “got it,” the BHB was pushed aside and is now used by less and less firms. Please feel free to comment. And if, perchance, you can offer a meaningful question to align with the total plan’s time-weighted return, or explain what it actually represents, “I’m all ears!”

Note that this isn’t the only GIPS standard metric I’ve criticized. I’ve argued that the aggregate method for composite construction not only violates the definition of a composite return, but has the potential to result in nonsensical results. The asset-weighted standard deviation, which the AIMR-PPS® (AIMR Performance Presentation Standards) encouraged yields a result that no one can explain. Fortunately the GIPS standards do not recommend it, but they also don’t discourage its use: they should.

The Standards are very important. Not only have they been adopted by most investment managers, but they are also becoming more widely adopted by asset owners around the globe. We support this. We only wish they could do a few things a bit better.

- In his dissertation, Pension Funds: Measuring Investment Performance. He did not coin the term time-weighting, however; that was done by the Bank Administration Institute two years later, when they published their Measuring the Investment Performance of Pension Funds.

- Back then, private equity investing was not common, so the notion of using the IRR for the manager would have not applied in most cases.

- This is an optional day where the our verifier conducts training, a gap analysis, and other activities to help a new client proceed towards compliance with the GIPS standards. To learn more about this, please contact Chris Spaulding (CSpaulding@TSGperformance.com).

Have an opinion? Please share it with Patrick Fowler.

Industry Dates and Conferences

2024 EVENTS CALENDAR

- May 21 – Women in Performance Measurement Meeting – New Brunswick, NJ

- May 22-23 – Performance Measurement, Attribution, and Risk Conference (PMAR) – New Brunswick, NJ

- June 12 – Spring Meeting of the Asset Owner Roundtable (AORT) – Las Vegas, NV

- June 13-14 – Spring North American Meeting of the Performance Measurement Forum – Las Vegas, NV

- June 27-28 – Spring EMEA Meeting of the Performance Measurement Forum – Athens, Greece

- November 7-8 – Autumn EMEA Meeting of the Performance Measurement Forum – Barcelona, Spain

- November 20 – Fall Meeting of the Asset Owner Roundtable (AORT) – Charleston, SC

- November 21-22 – Fall North American Meeting of the Performance Measurement Forum – Charleston, SC

For information on the 2024 events, please contact

Patrick Fowler at 732-873-5700.

- Artificial Intelligence and Risk: Should We Be Concerned?

- What’s Missing from Your Equity Attribution Report?

- ESG: Risk, Compliance, and Regulatory Reporting – Why Having the Right Data and Tools is Essential

- How are the New SEC Guidelines Being Practically Implemented and Applied?

- What to Know About the New GIPS® Guidance for OCIOs

- Essential Skillsets of the Performance Professional

- Methods and Styles of Reporting

- Benchmark Misfit

- Paths to a “Rich” Life

- How to Calculate Returns on Options, Futures, and Swaps

- GIPS Q&A

Institute / Training

Access All of TSG’s Online Performance, Attribution, Risk, and Python Content

With One Multi-Pass

Question 4: The proposed asset allocation ranges for the Required OCIO Composites have been created based on a widely used set of OCIO indices, which is built to include the most common 60/40 portfolio in the middle of the moderate bucket. Do you agree with these ranges, or do you think we should take a different approach?

Within the proposed required composite structure, we find this part of the structure to be the most problematic. In our experience, we believe most firms would find that these ranges are not reflective of their strategies. Firms should be allowed to determine these asset allocation ranges based on their strategies.

If the other elements of the proposed required composite structure are required in the final version of the guidance and asset allocation ranges are required, we feel strongly that these ranges should be dictated by the firm based on ranges more suited to their strategies.

That’s a Good Question

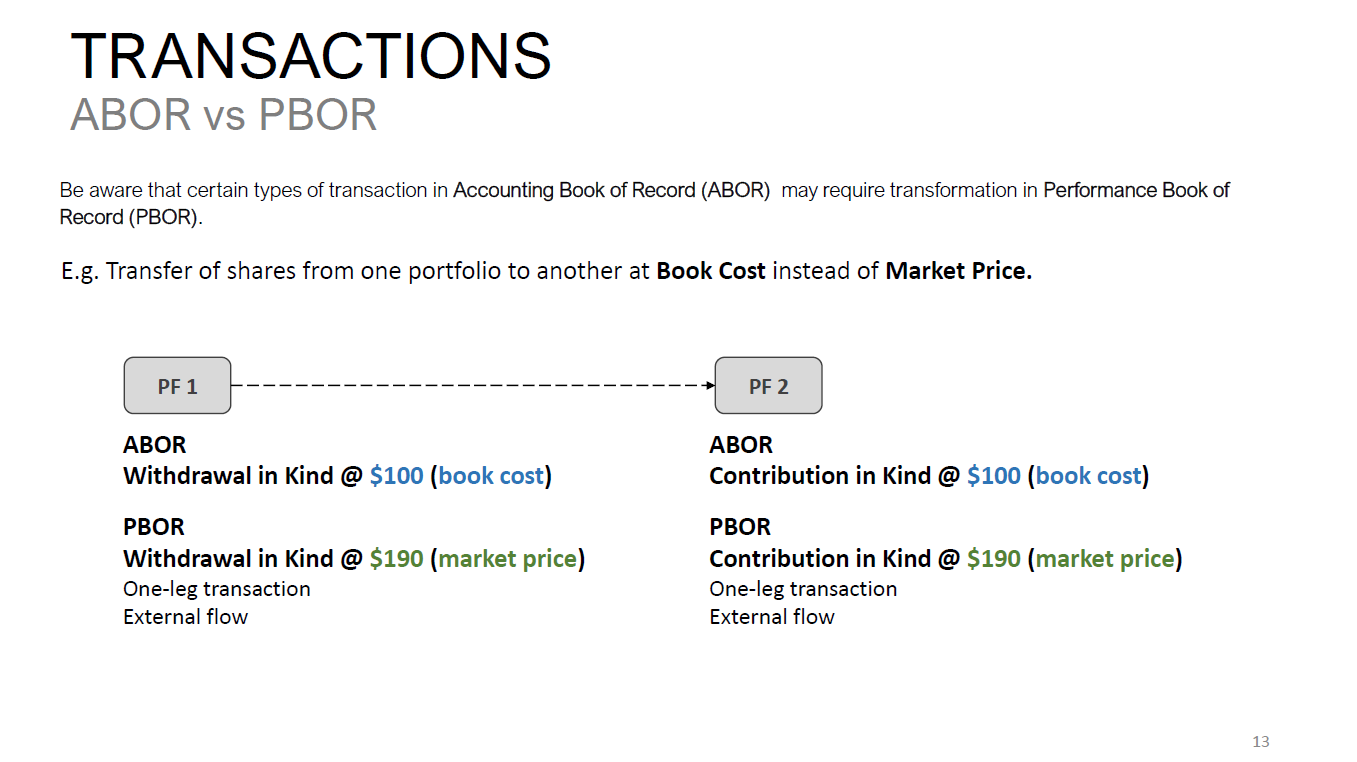

We are going through an exercise to figure out how an IBOR/ABOR(PBOR) solution works in the industry. I was wondering if you can help with any references you may have, or anyone that operates in this model.

TSG’s response:

Some quick thoughts

ABOR = Accounting Book of Records.

In some cases, the institution has their own “portfolio accounting” system in-house, which would constitute the ABOR. Alternatively, they rely on the custodian, who is the “Official Book of Records” (OBOR, if you will, though I’ve never seen it phased this way), and can constitute the ABOR for the institution.

IBOR = Investment Book of Records.

In some cases, when there’s an internal ABOR, it has limitations that can impede the investment process (e.g., disallowing trades to be done at certain times; not permitting restating history). And so, some institutions will incorporate a separate IBOR, that interfaces/reconciles w/the ABOR, but permits more flexibility for the investment team.

PBOR = Performance Book of Records.

In some cases, this is “welded on,” so to speak, to the ABOR or IBOR; that is, these systems come with performance functionality. In other cases, a separate system is used, that reconciles with the IBOR and/or ABOR, to provide the performance team the records they need. Again, we might see increased flexibility allowed, to ensure they are able to have the necessary data to provide accurate results.

Example.

Additional references: https://www.limina.com/blog/ibor-abor-pbor-cbor-differences

Please submit your questions to Patrick Fowler.

Potpourri

In The News

Performance Measurement Professional Survey

Article Submissions

The Journal of Performance Measurement® is currently accepting article submissions

The Journal of Performance Measurement is currently accepting article submissions on topics including performance measurement, risk, ESG, AI, and attribution. We are particularly interested in articles that cover practical performance issues and solutions that performance professionals face every day. All articles are subject to a double-blind review process before being approved for publication. White papers will also be considered. For more information and to receive our manuscript guidelines, please contact Douglas Spaulding at DougSpaulding@TSGperformance.com.

Submission deadlines

Summer Issue: July 12, 2024

Fall Issue: October 11, 2024

Survey Results from March’s Newsletter on Artificial Intelligence / Machine Learning:

- Did your department have an Artificial Intelligence (AI)/ Machine Learning (ML) initiative in 2023?

- We ran a proof of concept – 0%

- We deployed a solution – 50%

- No, but we have plans for 2024 – 17%

- No, we have no plans – 33%

- What area is the highest priority for using an AI/ML solution?

- Alternatives data – 80%

- Private Credit data – 0%

- ESG data – 20%

- Comments: Operational efficiency

- What is your organization’s biggest hurdle to implement an AI/ML solution?

- Costs – 33.33%

- Security Concerns – 66.67%

- Not a Priority –

GIPS® is a registered trademark owned by CFA Institute. CFA Institute does not endorse or promote this organization, nor does it warrant the accuracy or quality of the content contained herein.